There is a strong argument against the idea of the nostalgic sublime. If the sublime leads to a drive to act in new ways, due to the enthusiasm released by simultaneous feelings of terror and attraction to a strange and inexplicable event, then the backward looking and stultifying qualities of nostalgia disqualify it from sublimity.

The sublime is inspiration, not deflation. It is a fearful thrill, not a cosy regret. The sublime builds. It doesn’t wallow in the ruins of collapsed empires. The art of the sublime is modern; it rejects the past and summons a different future. The sublime is change, not regression.

Yet one of the most acute philosophers of the sublime, Burke, left us with a striking image for sublime nostalgia. Nobody would want to see London destroyed by an earthquake, he says, even less be there as it fell down. But many would come to visit the ruins, to experience terror and delight at the disintegration of a once great city: ‘… what number from all parts would crowd to behold the ruins.’ (Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, London: R and J Dodsley, 1757, p 27)

Burke chooses London to invite his readers to look at magnificence with foreboding, yet also to imagine joining the gawping multitude, later. This distance over time is important for him and for Kant, since it removes immediate peril. For Kant, this provides for reflection and reason beyond the sublime. For Burke, it explains how delight – the suspension of pain and threat – can be paired with terror.

There had been a minor but unnerving earthquake in London a few years earlier, in 1750. The tremors were followed by waves of rumour and panic. This ‘terror’ is Burke’s favoured term for the negative emotion accompanying the sublime, in counterpoint to the positive ‘delight’. Greater horror was to follow, in 1755, with the Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. Many philosophers searched for its meaning – most famously Voltaire in Candide.

Writing on the the Lisbon earthquake, Alexander Regier gives illuminating readings of eyewitness reports. He draws out the sublime content of their awestruck descriptions and its influence on later philosophies of the sublime:

By looking closely at texts by Burke and Kant, I will attempt to unravel the double nature of the sublime as a taming and domesticating force that ultimately relies on the destructive power of fragmentation. Lisbon and its shattering power haunt the secular and ‘progressivist’ character of Burke’s and Kant ’s arguments that has often been taken for granted in secondary literature.

Regier, A. (2010). Forces trembling underneath: The Lisbon earthquake and the sublime. In Fracture and Fragmentation in British Romanticism (Cambridge Studies in Romanticism, pp. 75-94). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511750434.004, p 77

The equivocal role of the sublime is typical. It will be important in judging the nostalgic sublime. When Regier draws attention to the ‘double nature’ of the sublime as destructive and pacifying, a further duality appears. The sublime is a concept created by Kant and Burke and an observed phenomenon. Like the revelation of a deep truth about us in a song or poem, the sublime is both made and uncovered. In defining the sublime, we partly bring about the idea and the experience. Do we want to make it nostalgic or not?

If it is nostalgic and hence backward looking, it is unlikely that the sublime will be straightforwardly progressive. Furthermore, I disagree with the description of Burke’s sublime as progressivist. It is to read him through a Kantian lens and thereby to underplay Burke’s attentiveness. There’s a deep empiricism to his observations on the sublime, where the feeling need not be edifying at all. It covers many different experiences, neither simply good, nor evil.

Releasing different processes to the beautiful, Burke’s sublime is an overwhelming and strained combination of emotions, indicating a special experience and its causes. This tension has moral and political consequences, but they are diffuse. When danger passes, delight has no particular goal or direction other than inward relief. It’s a reprieve, not a direct motivation – the pleasure of the lifting of pain, rather than the promise of new excitements.

In this sublime, terror and delight are connected by self-preservation. There is terror in the threat of destruction of the self, followed by delight at its salvation. This transition from pain to pleasure leads to many different feelings brought about by intense relief:

In all these cases, if the pain and terror are so modified as not to be actually noxious; if the pain is not carried to violence, and the terror is not conversant about the present destruction of the person, as these emotions clear the parts, whether fine, or gross, of a dangerous or troublesome encumbrance, they are capable of producing delight; not pleasure, but a sort of delightful horror, a sort of tranquillity tinged with terror; which as it belongs to self-preservation is one of the strongest of all the passions. Its object is the sublime. Its highest degree I call astonishment; the subordinate degrees are awe, reverence and respect, which by the very etymology of the words shew from what source they are derived, and how they stand distinguished from positive pleasure.

Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, London: R and J Dodsley, 1757, p 129

This passage contains some of the most significant aspects of Burke’s sublime. They are characteristic of his subtle observation, distinguishing it from cruder, though theoretically more bold, definitions given by Kant and others:

- Burke emphasises the mingling of different emotions and affects in the sublime, ‘pain and terror’, ‘delightful horror’, ‘tranquillity tinged with terror’, ‘astonishment… awe, reverence, respect’. In all of these, he is in pursuit of an accurate description of a complex phenomenon

- The object of the sublime matters because it brings about tensions between emotions. This means the scale and type of object is not decisive. The test is in the emotions, not the object. Burke detects the sublime across events, objects and arts, across different scales, places and experiences

- Burke’s sublime is emotionally dynamic. He speaks of degrees and strengths over time – ‘not present’ but ‘as they clear the parts’. Seeking to capture how terror diminishes, he describes rising and decreasing intensities of related emotions and affects

- Sublime experiences are like phobias and desires, not only in their attachment to unexpected objects, but in their unconscious operation on emotions felt over periods of time

- Terror and the release from it are about the destruction and saving of a self, understood in a broad sense as body, possessions, loves, mind and souls. Burke’s political sensitivities come, in part, from this drive to self-preservation of individual and social selves

- If we define progressivity as the search for universal improvement independent of selfish concerns, then terror and delight, undergone as powerful passions, pull us away from those universal aims and back to local concerns

- In prioritising preservation, Burke avoids the lure of sublime sacrifice, of action independent of concerns for self and kin – as in Kantian duty. For Burke, the self comes first, but not at any cost, since it is emotionally dependent, leaving the way open to unselfish acts

- The self is never alone in reprieve from danger. It is attached to the causes of its passions, extending into them. Self-preservation is necessarily shared, through the living and inert things needed for life, through passions distributing the feeling of the sublime between individuals, and above all for Burke, in sympathy.

The threat to the self is not simply negative and to be repulsed. It is rather something we are drawn to, yet put at risk by – a fascination in terror. This sense of thrill, when followed by delight, pushes the self into experiences that are more than enjoyed. They become identity-defining, like a great task looked back upon in relief and joy, or the turmoil of a disruptive experience turning into love.

The demarcation of identity through intense experiences prepares the way for a nostalgic sublime. It becomes possible to look back at sublime moments with a combination of fondness and regret at their passing, because they made important contributions to our values, such as the sympathy of comrades, after weathering a storm through joint effort:

Sympathy is the communion of selves in shared experiences. In sublime sympathy, as felt for the victims of an earthquake or tsunami, or looking back at a shared ordeal, the self enters into an imagined community and a real bond.

If Burke is to be considered progressive, it is only in this unstable coming together of the will to conserve and passionate dependencies. This togetherness is far from Kant’s disinterested and rational universalism. It is interested, since driven by the passions. As attached to a particular experience, it can only approach universality if gradually shown to be shared by all.

A bond of sympathy may be at odds with other emotional affinities – family, clan, friend, compatriot, comrade, herd, land. It may also be unstable, because it takes place in a flux of experience – the to-and-fro of allegiances over time. Two features of the political implications of Burke’s sublime follow from these competing demands. They are both significant for modern politics and I discuss them at greater length in The Egalitarian Sublime.

First, Burke’s wavering relation to colonialism depends on perspectives of sympathies. His relentless opposition to the East India Company and sympathy for the victims of its rapaciousness is countered by his romaticised Indian sublime, colonial in its sentiments and judgements. Sympathy is located, leading to clashes between different allegiances.

Second, sympathy shapes Burke’s ambiguous relation to the French revolution. Revolutions can be sublime: they are terrifying, yet carry positive aims and communal emotions. There is delight at the suspension of revolution – in failure or success. However, revolutions are threats to other types of sympathy, dependent on shared order, culture and tradition. For Burke, these are preconditions for any sympathy at all.

Against the sublime of directly experienced grandeur, for an understanding of the nostalgic sublime it is critical to register how conservative sympathy can have sublime roots and connections; for instance, in the delight of a settled society after the turmoil of liberation, civil war or desperate defence, ‘in a state of much sobriety, impressed with a sense of awe, in a sort of tranquillity shadowed with horror.’ (A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, p 7)

The sublime is often presented as lonely, an experience of solitude and fragility in the face of overwhelming power. Burke understood how this cannot be the case. Its power works through common bodies and shared environments.

Towards the end of the Enquiry, his reading of Milton demonstrates the sublimity of language, in deeply felt sympathy around death: ‘The idea or affection caused by a word, which nothing but a word could annex to the others, raises a very great degree of the sublime; and is raised yet further by what follows a “universe of death”.’ (A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, p. 183) Even when the sublime is depicted as a lonely experience, the common effect of this depiction depends upon sympathy:

Where Kant requires distance for reason to flourish, Burke perceives how the intense and contradictory feelings of the sublime linger in reason, giving it motivation and guidance. For the former, distance brings about separation; for the latter, it allows for transitions and tensions of emotions and ideas.

Kant’s pre-critical natural science divides the emotions from scientific examination. This lends coldness to his three essays on earthquakes. He advocates rational and science-based responses to natural disasters, including accepting their inevitability. History has a role in recording horror, suffering and beliefs, but it must remain distinct from the explanatory power of the sciences and their task of rebuilding after quakes:

Would it not be better to conclude that it was necessary for earthquakes to occur occasionally on the Earth, but it was not necessary for us to erect splendid houses on it? The inhabitants of Peru live in houses that are built with mortar only up to a low height and the rest consists of reeds. Man must learn to adapt to nature, but he wants nature to adapt to him.

Immanuel Kant, ‘History and Natural Description of the Most Noteworthy Occurrences of the Earthquake That struck a Large Part of the Earth at the End of the Year 1755’ in Immanuel Kant, Natural Science, Eric Watkins (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 2012 [all three of Kant’s earthquake essays pp 327-773] p 360

Kant’s reports on the science of earthquakes do not add original empirical research. Their tone is dogmatic, with certainty of judgement and knowledge, perhaps unwarranted, given the falsehood of much of what he took to be true.

Against the separation of science and emotion, Jane Madsen’s PhD on the ideas of the arch and its collapse demonstrates how Kleist combines moral and aesthetic sensitivity with science. Inspired by Kant’s critical philosophy and its uncertainty, when compared to the pre-critical essays, Kleist’s disquieting story ‘The Earthquake in Chile‘ traps its characters under a tragic ‘accidental arch’ leaving us with ‘the compelling and paradoxical image of the stones that keep the arch standing while wanting to fall…’ (Madsen, Kleist and the Space of Collapse, p 224)

Madsen draws on Reinhardt and Oldroyd’s studies of Kant’s science (‘Kant’s Theory of Earthquakes and Volcanic Action‘). Their scientific analysis contrasts with Rachel Jones’ reading of Luce Irigaray and her reconfiguring of the Kantian sublime into wonder (anteceding Genevieve Lloyd’s more recent return to wonder from the sublime) where ‘the sublime encounter with an earth that moves need not necessarily be horrifying or traumatic but may instead hold the promise of transformative and even shared adventures in difference.’ (Rachel Jones, Kant, Irigaray and Earthquakes, Symposium, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 2013, pp 273-99, pp 298-9)

Kleist’s story adds the terror of mobs and of untethered power to the sublime of earthquakes. Other thinkers speak of terrorism, war and the Holocaust as sublime. Gene Ray has discussed these in a number of publications covering a great range of events and thinkers (for instance, in his piece on the Lisbon earthquake, Gene Ray ‘Reading the Lisbon Earthquake: Adorno, Lyotard and the Contemporary Sublime’ The Yale Journal of Criticism, Volume 17, Number 1, Spring 2004, pp 1-18).

In The Egalitarian Sublime, I caution against identifying the sublime with terrorism – a term that suffers from dangerous and politicised vagueness. The variety of sublime experiences in Burke should not be confused with imprecision. His observations cover many cases, but always with rigour about the kinds of terror and delight at work in them. There is no delight in the grips of violent terror and death, or among those who celebrate the demise of others and of themselves in senseless annihilation.

Whether pre-critical or later, Kant’s progressivism fits the argument that the sublime is not nostalgic. Reason moves on from the sublime, from its object and its emotion. It only retains the idea that the faculties can be overwhelmed and the deduction that reason alone can rise above and make sense of this turmoil. Reason is energised and confirmed by the force of its victory over the sublime – an argument redolent of arrogant conquest.

As Regier demonstrates, there will always be a fatal contradiction in Kant’s thought when reason rises above the sublime. Kant’s argument requires remnants of the sublime experience within ideas of reason, yet it also asks for these hauntings to be forgotten. This inconsistency is a stubborn legacy for later theories of the sublime, to the point where it can be projected back – mistakenly – upon earlier thinkers like Burke.

The theme of haunting between supposedly separate concepts in a philosophical argument is developed by Derrida, notably in his Spectres of Marx. Reason will be haunted by sublime passion – for instance, in its self-certainty – not because sublimity is directly present in reason, but because they were forged together:

To haunt does not mean to be present, and we must introduce haunting into the very construction of a concept. Of every concept, starting with the concepts of time and being. This is what we would here call hauntology.

Jacques Derrida, Spectres de Marx, Paris: Galilée, 1993, p 255 [my translation]

Derrida’s point is that concepts affect each other in their joint construction; to the point where they cannot be separated later, because each ‘plunges the other into mourning’.

Reason mourns sublime catastrophe, even if it feigns not to. If the sublime leads to fragmentation, such as rootless despair in the wastelands of the Lisbon earthquake, then it cannot lead to the unification and improvements afforded by reason, unless reason can obliterate earlier fragmentation. If it does that completely, though, it also discards the force gathered from its overcoming of the sublime.

Haunting is positive for Derrida – a more faithful sense of time and existence. It is a finer understanding of the interdependence of concepts and of their emotional provenance. In the case of reason, the ghosts of sensual experience are a reminder of the fragmentation of the sublime, of the conjunction of reason’s fragility, capacity for failure and power to overcome. This takes reason closer to wisdom and away from the follies of certainty:

The pervasive sign of these contradictions is the idea of the detached yet invigorated spectator. In Kant’s theory, the sublime is for onlookers or bystanders. They are protected from immediate threat of destruction, yet also sense – then understand – a transition from the force of the sublime to the power of its rational overcoming:

Thus any spectator who beholds massive mountains climbing skywards, deep gorges with raging streams in them, wastelands lying in deep shadow and inviting melancholy meditation, and so on is indeed seized by amazement bordering on terror, by horror and a sacred thrill; but since he knows he is safe, this is not actual fear: it is merely our attempt to incur it with our imagination, and in order that we may feel that power’s might and connect the mental agitation this arouses with the mind’s state of rest. In this way we feel our superiority to nature within ourselves, and hence also to nature outside us insofar as it can influence our feeling of well-being.

Kant, Critique of Judgment, Werner S. Pluhar (trans.), Cambridge: Hackett, 1987, p 129

This is a deeply implausible account of spectators, because it depends on lack of concern for outcomes and on dispassionate detachment, at the very point where an intense experience is working on us. Kant gives us an overly simple account of spectatorship. He confuses a second-hand experience – to be an onlooker – with a third hand one – to reflect critically and morally about our states and the states of others as spectators. The problem is that these two states also haunt each other. This haunting has a characteristic condition: bad faith, or to treat oneself as oneself, but also as another.

Kant fails to take account of the unconscious effects of violence and action, and the deep traces that follow from them. We absorb threats, suffering from the destruction of places, people and ideas we hold dear and have sympathy for. Worse, we consume violence done to others, vicariously enjoying unjust victories, and feeling pride at unearned security. Even in delight, the sublime experience is a trauma, not a dependable occasion for the cool assessment of rational superiority.

The young Burke had been a spectator of sublime catastrophe, when the river Liffey flooded, threatening his family home. Luke Gibbons links this experience to his later philosophy of the sublime (Luke Gibbons, Edmund Burke and Ireland: Aesthetics, Politics and the Colonial Sublime, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p 2). Against Kant, to witness a flood is to be marked, even if we are in a secure position above the waterline. It is to absorb the force, deadliness and devastation of mud and water – to retain it deep within us for later recall.

It is possible that Burke was alluding to Lisbon in his observations on the sublime and London. His concern is not with immediate terror but with the sublimity of the ensuing ruins. Unlike Kant’s, this sublime is passionate, involved and formed directly by a wide range of experiences and sensations. The archetype for these sublime ruins is neither the English capital, nor Lisbon. It is the same for us as when Burke spoke of ‘her ruin’, in Reflections on the Revolution in France.

Rome’s ruins have long been the occasion for a nostalgic sublime in art and literature. Crowds come to see the remains of empire in ever greater numbers, collecting at the same viewpoint:

Regretful and nostalgic ruins cannot be sublime for Kant. His theory combines imagination and reason, but reason experiences a victory free of torment and guilt, as it rises above nature and guides moral resolve:

Hence nature is here called sublime merely because it elevates our imagination, [making] it exhibit those cases where the mind can come to feel its own sublimity, which lies in its vocation and elevates it even above nature.

Kant, Critique of Judgment, p 121

Against this elevation of reason, sublime ruins call us back and feed nostalgic imagination. Thinking of loss and decay, of the power of nature and of the natural forces in us that unleash war and destruction, we yearn for a return to past grandeur.

Emotions of sadness and regret, clinging to the past through its ruination, do not fit the progressive qualities of Kantian reason, as applied to morals and politics. Kant’s sublime drives towards a new world, not pictured through the imagination, but rather brought about through moral and political acts, given maxims and ideas by a form of reason independent of any empirical present.

To purify his rational sublime, Kant shows how it can be freed from sadness. He demonstrates this just before a respectful, yet ultimately formulaic, rejection of Burke’s empiricism. Starting with a remark by one of his favourite sources for sublime experiences, Kant distinguishes two kinds of sad feeling: ‘Saussure, as intelligent as he was thorough, in describing his Alpine travels says of Bonhomme, one of the Savoy mountains, “a certain insipid sadness reigns there.”‘ (277)

Saving Saussure from himself, Kant argues that he must have known ‘interesting’ sadness too. The difference lies in the moral ideas attached to each emotion. Insipid sadness leads to moral abandonment, whereas interested sadness has a moral point: ‘… even grief (but not a dejected kind of sadness) may be included among the vigorous affects, if it has its basis in moral ideas.’ For Kant, the vigour of affects does not correspond to their felt intensity. An affect is vigorous through the strength of moral ideas, reason and progressive action.

Sympathy is to Burke what reason is to Kant: the foundation for the moral and political role of the sublime. They are therefore at odds with each other in the most basic way. After dismissing sympathy as vigorous, Kant returns to Burke’s empirical sublime. This rejection of sympathy may seem absurd; it ignores ample evidence of human bonds based on fellow feeling. Nonetheless, there is a shared basis with Kant’s wider argument against Burke’s empiricism. Sympathy, like taste, can never reach universal assent, if it is grounded in particular subjective experiences, because there will be no just way of resolving disagreements between different experiences.

According to Kant’s argument, when we appeal to taste we expect universal assent, as in the phrase ‘this is good’ uttered to garner agreement. Taste must therefore ‘be based on some a priori principle… and we can never arrive at such a principle by scouting about for empirical laws about mental changes.’ (Critique of Judgment, p 140) If we are faithful to Burke and to Derrida’s idea of the haunting of reason, the reply is that all we can do is scout for such laws. There is nothing else – no ‘a priori’ untroubled by the spectres of experience. Kant’s sublime is a fictional pretext for a false claim to universality.

Prevalent around the ruins of supposed greatness, nostalgia is an ambiguous term. It has been in use for at least 250 years, but acquired a new sense from the 1950s onwards. In contemporary usage, it can mean a mild and pleasantly bitter-sweet, wistful, reminiscence of the past.

Before this shift in meaning, nostalgia was a forceful affliction, an extreme desire to return home. In Burke’s time, sailors on long trips would experience nostalgia as a greatly debilitating medical condition: ‘An unconquerable desire of returning to one’s native country, frequent in long voyages, in which the patient becomes so insane as to throw themselves into the sea, mistaking it for green fields or meadows.’ (Erasmus Darwin, Zoonomia, 1794, quoted in Helmut Illbruck, Nostalgia: Origins and Ends of a Disease, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2012, p 117)

The ‘nost’ (nostos) is from the Greek for ‘return’. It stems from the trials of the heroic and difficult journey home, in Homer’s Odyssey, above all. ‘Algia’ (algos) is Greek for pain, prolonged as in an ache. Medically and in related usage, nostalgia is a powerful and painful pathology. It is overwhelming homesickness, taken to the point of unreason.

Home can stand for many things. In the case of nostalgia, it captures the sense of reaching for where we once belonged, and for what we once valued. This is not necessarily where we came from – our homeland or birthplace – but rather where we feel a need to be. We may never even have lived in this ‘home’, nonetheless we are driven to return to it.

This latter meaning comes out most strongly in the French expression nostalgie de la boue (mud nostalgia), a desire for the gutter, for what is lowly, disdained, dirty and impaired. Some view this nostalgia as affected – a playing at poverty – but that’s not right. At its most powerful, nostalgie de la boue captures our sexual drive, visceral attraction and debt to filth and, more importantly, to what has been assessed as filthy.

For the sublime, the stronger usage of nostalgia and the many meanings of home are the right ones. Sublime nostalgia is powerful and painful. It has no proper object, but follows from a distortion of partial experience by imagination, bringing together the sorrow of loss with a desire to regain. Burke’s description of London after the quake captures this sense. The ruins are testimony to the longing for a return to imagined splendour, along with its impossibility.

The combination of loss, desire and impossibility is evoked in the Portuguese feeling of nostalgia and melancholic longing, saudade, influenced by the destruction of Lisbon at the height of its greatness, an event that overshadows and sets the tone for the city thereafter:

I don’t mourn the loss of my childhood; I mourn because everything, including (my) childhood, is lost. It’s not the concrete passing of my own days but the abstract passage of time that torments my physical brain with the relentless repetition of the piano scales, from upstairs, terribly anonymous and far away. It’s the huge mystery of nothing lasting which incessantly hammers things that aren’t necessarily music, just nostalgia, in the absurd depths of memory.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, trans. R. Zenith, London: Penguin, 2002, text 266

Through the pseudonym Bernardo Soares, a bookkeeper and solitary writer, Fernando Pessoa defends a debilitating, yet also life-affirming, nostalgic sublime: ‘Nostalgia for the pools of unknown farms… Tender affection for what never happened.’ (141-4)

This is not nostalgia for a bygone age, preserving the possibility of a successful return. It is rather a yearning for a past shorn of any positive content, where memory actively hollows out what has been – Deleuze would call it a becoming-imperceptible in the pure past.

Pessoa adds something important and strange, something I cannot do justice to here. He feels the importance of a perverse, ‘absurd’, kind of memory: a remembrance of things now impossible. This perversity is also a Deleuzian theme, but the writers part around the question of how to live on the very edge of nihilism.

Pessoa’s invention of nihilistic yet undespairing nostalgia is a manifesto against Romanticism:

The fundamental error of Romanticism is to confuse what we need with what we desire. We all need certain basic things for life’s preservation and continuance; we all desire a more perfect life, complete happiness, the fulfilment of our dreams and …

Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, p 53

When taken to bolster romantic images of the sublime, nostalgia serves the worst self-deception, where an idealised past is longed for and acted towards, at the expense of the present and future. This nostalgia is a state of mind ready for propaganda, a distortion of life in return for shallow comforts, fleeting safety and the illusion of rightness, masking vicious self-interest.

I started with an image of London during the Blitz to match Burke’s insights to Pessoa’s fusion of nostalgia with memory and permanent loss. The ruins are sublime because we cannot get the past back. This is the deepest political and existential danger of the nostalgic sublime – some will still wish to return to a perfect past and others will happily sell it to them, for a high price cloaked as a bargain.

There was neither cause for sublimity, nor nostalgia, in the crashing buildings, exploding bombs, sirens and panic during the successive bombings of the Second World War. Many Londoners – many city dwellers throughout Europe – became refugees while their loved ones stayed on and helped demolish their shattered homes and make them safe, or died in relentless sieges and fire storms.

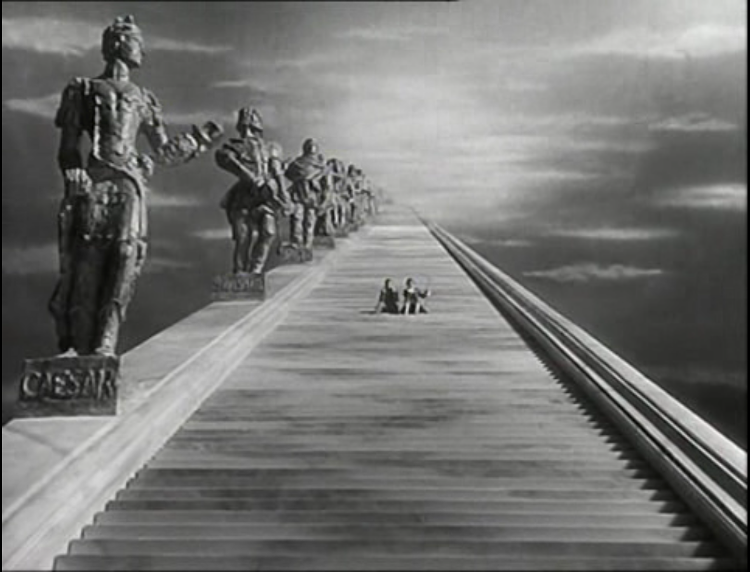

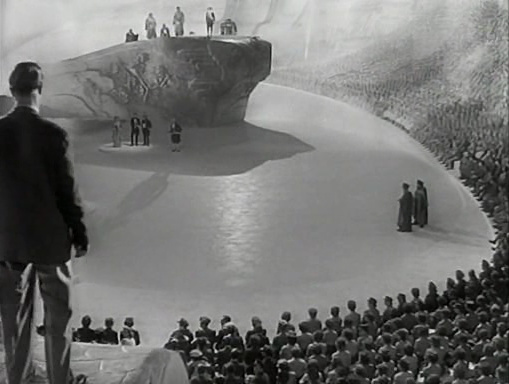

It would take well over a decade of drab and difficult reconstruction, weighed down by war debt, to remake London differently and to forge a fairer version of modern Britain. Yet nostalgia for pre-war and wartime empires has continued to grow, fostered by the press, politics and some art works, above all war films, such as the sublime images and fortitude of A Matter of Life and Death by Powell and Pressburger:

The cinematic sublime is made and the nostalgic sublime is constructed, fostered and exploited over time. This means we can choose to have it or not. Any such decision will be political as well as aesthetic and existential, not only about art and individual lives, but more importantly about common sympathies and actions.

Returning to my earlier definition of sublimity, from the study of manifest destiny (another disastrous political association for the sublime) I will conclude by arguing that we should not choose the nostalgic sublime. It leads us astray, traps us in a deceptive past, a stunted present and a future shorn of its better possibilities.

A sublime event is a context, with a catalyst, leading to an emotional tension, followed by a drive, an aim and an action. According to this definition, the nostalgic sublime stands out from other versions as follows:

- The environment for the nostalgic sublime is defined by memory. This can be through a form of inner recollection, but more often it is mediated by an art form such as film, or more crude images bordering on kitsch or propaganda;

- The catalyst is a dissatisfaction with the present, combined with longed for features of the past reconstituted in imagination;

- The emotional tension is between sadness, regret and longing, and hope, enthusiasm and enjoyment. The first three mark the loss of past experiences and values. The last three stem from the possibility of regaining it;

- The drive could be identified with the desire to return, but this would be incorrect. For nostalgia, the return is thwarted and the drive focuses instead on images of the past, rather than the past itself;

- The curtailment of the drive and its restriction to specific images limits the aims of the nostalgic sublime to an imagined past, unlike other forms of the sublime that can transfer to aims distant from their environment;

- The acts following on from nostalgia are similarly limited, drawing the present and the future to the image of the past, rather than experimenting with new constructions.

Taken together these points not only characterise the nostalgic sublime as limiting and disempowering, they also point to its dependence upon distortion and falsification. It veils the present, curtails the future and betrays the past.