[To give a sense of the bande dessinées referred to in this discussion I have included covers and links to publishers. Many of them give sample pages of their books on their websites, should you want to follow them up. I make no financial benefit from these links. They are included for academic reference and general interest.]

This post is a longer version of a talk given at the Posthumanism and the Art of Multiplicity symposium and book launches at Trinity College Dublin on 20 September 2023. It is partly in response to the volume of essays Life in the Posthuman Condition: Critical Responses to the Anthropocene, edited by S. E. Wilmer and Audronė Žukauskaitė.

My remarks were prompted by the thoughtful unpicking of the concept of the posthuman in the chapters of the volume. Nonetheless, and despite their wide range, they had a conflict running between them and sometimes within individual chapters. Was the posthuman condition a passage into new possibilities, or the arrival of a terminal event?

Was it an opportunity for collective reinvention, beyond the classical and destructive distinctions established by the human (Man/animal, Man/nature, Reason/madness, Body/technology) or a moment of reckoning for our acts and their devastating effects far beyond the human realm?

I had been thinking about this kind of conflict for a while, for two connected reasons. First, it encapsulates a criticism against Deleuze’s philosophy of multiple times. If foreseen doom (or salvation, for that matter) is the primary experience of time, then times denying the arrow from past to disastrous future are mistaken.

Second, for my work on a timed logic after Deleuze, there is another more pointed criticism. It is much easier to imagine time as running in many directions than thinking of those directions as physical facts. Might it be the case that the multiplicity of times is only imaginary. Deleuze’s philosophy of time would then be a form of idealism, drawn from fictions by Lewis Carroll (every direction at once), Borges (time as forking paths) and Nietzsche (eternal return)?

To consider this critical angle, I wanted to explore how times work in art and then see whether this could be extended to the physical world, counter to claims for differences between fiction and reality. Is time the same in ideal and material worlds? Do they share multiple times?

Despite its dominance in studies of time in Deleuze, I aimed to avoid cinema. This is not because film is a poor source, but rather that it is a well-worn one. There is value in considering different arts, less adapted to the manipulation of the experience of time, in cinematic flashbacks for instance, and therefore less prone to confirm theses about multiple ways of living in time.

I will hence study time and reading in bande dessinée (BD) as an example of experiences of the multiplicity of times. The cartoon book, comic strip, graphic novel or mixed media book is now a mature form, but it is underappreciated as an explanatory and inspirational source. Despite its minor status, it deserves elevation to ‘ninth art.’ One of the reasons for this is what it can teach us about time.

My argument is that despite an apparent direction for “reading” and interpreting bande dessinées, and despite their fictional aspect, their multi-layered form connects them to the real, while their frame, drawing and text structure interrupts, reconfigures and multiplies flows of reading and of time.

If montage is an assembly of different parts, giving specific directions to time and to works, even though they can be in unusual directions, démontage (dismantling, in French) undoes constructed and habitual patterns. It thereby prepares for new assemblies and multiple times.

I don’t think the latter concept has been used in this context before, though it is used in the sense of unpicking the montage of a film. In this usage, montage is well known as an editing technique for assembling images for a specific purpose, often narrative or emotional.

Particularly open to démontage, because its structure is already partly dismantled, a bande dessinée doesn’t have a strong predetermined flow hiding its parts. This gives readers a great deal of interpretative, perceptual and creative leeway when compared to other arts.

However, BD remains in contact with reality. This contact can be edifying, critical and creative; all the more so when expectations with respect to time can be undone through the experience of “reading” a BD. Right or wrong, the starting point of a critical creativity is raising doubts about things we take for granted.

Perhaps surprisingly, for a medium associated with childhood, BD invites deep questioning about what we take to be reality. That’s not as remarkable as it seems, when we remember that youth is a period of learning and questioning – marked more and more by BD in all its forms and across many facets of teaching, learning, and delight in art and literature.

I have put reading in scare quotes here to highlight a problem and give an illustration of my argument. We usually, if wrongly, think that reading has a direction, from beginning to end. Poetry and experimental prose have long shown this to be illusory. With a bande dessinée words, images, frames and pages can be dismantled and reassembled in many directions and rhythms: an operation of démontage and montage by readers.

More than in cinematic arts, but also literature where narrative flow is more dominant, the ability to dismantle the montage or assembly of the original BD makes it vulnerable to new ways of scanning it: montage and démontage go together in cycles giving readers the power to intervene on times and directions.

This is more like a walk round a gallery or through a sculpture park. We can take a pre-set path, as given by historical epochs, for instance. We can also halt at just one work, or go through disordered loops: skip, stop, start again, go back, jump, forget, focus, zoom in, zoom out, absorb passively, or actively.

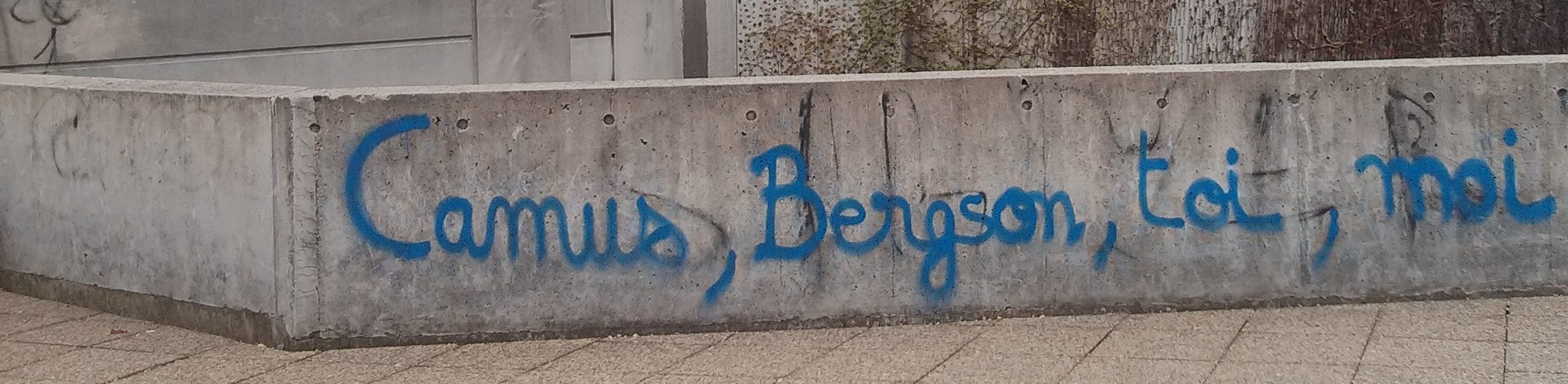

Démontage and montage are the reader’s contribution to a BD. It is how a bande dessinée is experienced, even when we read it from front cover to back, because words and images filter into us and remain there, as multiple image and word happenings, alongside our movement with the work, both conscious and unconscious. This is one of the reasons BDs are so well suited to exhibitions and street art: they support and encourage division and reconfiguring.

Doesn’t this capacity to disrupt patterns distance BD even further from reality? To give the strongest version of the accusation of idealism, a disadvantage of BD when compared with film is its apparent distance from the actual world. This is a greater barrier to equating fiction and reality. It is harder to confuse real things with a collection of drawn images, with their created lines, colours, texts and figures. A bande dessinée is strikingly a made object: a confection of disjointed spaces, invented images and words.

As a recording of the action before the lens, the camera once seemed like a window on some kind of reality. This was only a resemblance. It led to famous and playful versions of window effects in cinema, by some of the most ingenious users of montage and its effects.

With animation and computer generated images the age of apparent transparency is long gone in cinema.

Lacking that early windowlike quality or even the absorbing properties of text fading away into inner voice, the drawn image seems more fictional, less direct than the recordings of film, photography, spoken word, or written testimony. Yet, all these effects can only be relative to varieties of experience.

In an age prior to photography, sketches, drawings and engravings were powerful visual testimony; they still are in some of the most urgent and difficult environments, such as court rooms, the role of drawing in hospital settings, and the expression of suffering by children.

Many bandes dessinées set these attributes of testimony, learning and healing in motion. The necessary fiction of a combination of drawing and text is no bar to revelation of fact and truth, to uncovering experience, passing comment on it and contributing to new realities.

Shaun Tan’s art, starting with his wordless graphic novel, The Arrival, shows the power of BD to reveal truths about urgent events, such as the plight of refugees, but also better ways of living together, such as the respective kindness of welcomed and host, where an exchange of unexpected gifts defeats fearfulness.

Tan achieves this through magical fiction and, in an age of suspicion and racist retrenchment, his art prepares the way for a better reception for those who arrive destitute on foreign shores. When children learn through his works, the future for extremist nativism becomes ever more narrow, ever more dependent on false memory and confected urgency.

I hesitated to post the above link to a horrifying Trump speech, but his mendacious fearmongering is typical of global right-wing trends. Against this miserable violence, here is further reading on Tan, children’s literature and politically engaged magical realism: https://www.ft.com/content/b60e8c32-64cb-11e6-a08a-c7ac04ef00aa. And here is a generous and enlightening interview with Tan: http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/shaun_tan)

As Tan shows, BD can play powerful roles in response to real problems, but what is distinctive about this response when compared to other arts?

There is no fully satisfactory English translation for the French expression ‘bande dessinée‘, long in use in France, Belgium, Canada and Switzerland. In other countries with long comic traditions, such as Japan (manga), Italy (fumetto) or Spain (historieta), a similar lack of an equivalent to the French term risks too narrow definition of the art form.

The advantage of ‘bande dessinée‘ is its breadth and lack of settled meaning beyond the practice of a drawn strip or even a single image. In this definition, there is no requirement for humour (comic) or specific style (cartoon, manga) or speech bubbles (fumetti) or brief story (historieta) or physical form (album) or art form (graphic novel). There isn’t even a need for words, since there are many wordless bandes dessinées. Nor are images prerequisites. There are strips of text only that still qualify as BD.

For BD, again as in poetry and some experimental literature, text is explicitly given as an image and with images. This is a property expandable to any text, shown by dependence on font, backing, colour, spacing, setting, rhythm, direction of reading and direction of viewing. Bande dessinée is a youthful art, in years and audience, but it is also a return to the original state of text, where words emerge with and as images and affects, rather than describing them.

In early illuminated texts, such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Manuscript (famous for its final note on publication giving its date and patron – its colophon) text and image are inseparable, ‘an iconographic and stylistic unit.’ They complete one another: the text is also sensual imagery; the image is additionally a text to be read:

This manuscript is not only valuable due to its colophon, but also because it is one of the very few completely preserved Indian Buddhist manuscripts: the illustrations and text are complete and the original covers are preserved. The illustrations of the text and the covers form an iconographic and stylistic unit.

https://www.asianart.com/articles/allinger/index.html

The intimate link between image and text has neither been lost nor overcome since the long centuries dominated by illuminated texts. Like a panel in a BD, the mood behind a scribbled missive can be sensed, if often wrongly, from the shape of pen strokes long before the letter is consumed as text. The same is valid for signatures; we practice projecting affects in our scrawls and missives. It even holds for our seemingly aesthetically uniform electronic messages.

The significant point, though, is that there is no necessary direction of assembly or disassembly for this relation of text and image, or for the appearance of text as image. More than any narrative, or even focalisation through different perspectives and perceptions, the image leaves readers and viewers with a freedom to scan as they please yet remain in the work.

Démontage and montage is therefore a more radical combination than focalisation. For the latter, there can be many different perspectives prior to narration and they can be at odds with one another, but there are still limits to focalisation according to types of perception and perceiving figures.

Coming before any narrative and perceiving figure in the work, démontage needn’t submit to their forms or flow. Once text and image coexist and once text is an image, the only condition for reading is open space, apt for any new distribution of directions and focal points.

Deleuze called this kind of spatial openness a ‘nomadic distribution’. It is a spatial distribution unfolding without external grids or directions. A nomadic distribution sets down its own lines. It bifurcates at points – singularities – made significant solely by the distribution. Any rule or pattern is fixed only after the nomadic trail:

Then, there is a totally different distribution that we should call nomadic, a nomad nomos [law or custom], without property, enclosure or measure. Here, there is no longer sharing and division of something that has already been distributed, but rather a spreading out by those who distribute themselves, in a limitless open space, or at least without precise limits.

Gilles Deleuze, Différence et répétition (Paris: PUF, 1968) p 54 [My translation with ‘sharing and division’ for the French ‘partage’ and ‘spreading out’ for ‘répartition’]

Five remarks are helpful here; three are about interpretation, one is an implication and one is about legitimacy, reality and illusion.

First, the order in which events take place is important for a full understanding of the concept of a nomadic distribution. If a space has been prepared beforehand, if it has well-defined internal and external boundaries, a movement controlled by them cannot be nomadic.

For nomadic distribution, it is essential that features of the space significant for the distribution only emerge with its movement through the space.

Second, a nomadic distribution is not about an allocation of resources, even after the nomadic distribution has taken place. The movement is not about sharing out divided goods, but rather about lines connecting singular points; that is, series of transformative encounters that can only be experienced, never weighed and distributed as property with a common value.

This matters for BD because it means that reading needn’t be a sharing of common meaning, universal values or general truths. The nomadic distribution is what Deleuze calls an ‘individuation’: to become a fluid and multiple individual in conjunction with the work.

Third, even if it appears that a sole actor moves through a space this individuation is not alone, because it isn’t a single static identity. As the nomadic distribution spreads through multiple transformative events, many movers are distributed, even if they give the illusion of being one, and even if they give the illusion of not moving at all. They stood still and their shadows moved over the shifting waves of sand in mysterious patterns.

Fourth, if it applies legitimately to a space, time is an external ordering for it. For instance, if events in the space can be measured legitimately according to an external time such that we can define units of space according to units of time (kilometres per hour), then the measured distribution is not nomadic.

Why do I say ‘legitimately’? In the quoted passage, Deleuze uses the Latin ‘nomos’ standing for law or custom, contrasting law as nomadic and as external limit. Later, when working with Guattari, this becomes the conflictual relation between nomadic (molecular) lines of flight and external (molar) norms.

Legitimacy indicates a problem raised by the following objection. If a nomadic distribution is constrained as nomadic, does it really follow its own lines in open space and time? The stress on ‘as nomadic’ is designed to avoid the mistake of confusing external and internal obstacles.

There can be no end of constraints on a movement, but this doesn’t imply that its internal directions are blocked or directed. It’s just there are obstacles it must avoid. The problem becomes serious if an external power can legitimately be said to have directed the nomadic movement. You thought you were drifting but they were running you all along.

So, fifth, a nomadic distribution takes place within constraints it must escape from as it spreads out in open space and time. This doesn’t mean that all such distributions are spectacular revolts; on the contrary, they can be unapparent, almost imperceptible, ways of unfolding. The test is whether independence is real or illusory, whether an external power has held sway or not.

All this this implies that any nomadic distribution must also be a distribution in open time, time without pre-set order, or the multiple times I have been describing as Deleuze’s timed logic.

The objection around real or illusory nomadic distributions can be put in practical terms about BD. Every image and text has distinctive features. How then can a reading be said to be open and nomadic, since it is limited by those features? It all depends whether the distribution is produced by those external features or whether its internal unfolding is new, creative and self-driven.

For Deleuze, a nomadic distribution is a creative passage through singular points. These can appear to be fixed features, but the distribution transforms them into novel events. In BD, a new reading occurs when text and image have new effects with the reading. The reader changes and becomes different with the work. Readers become multiple and changing individuals, at odds with the established order of the world while challenging and changing it.

For example, any webpage or social media communication is shaped by prior aesthetic decisions and predetermined features altering its impact. Meaning comes across thanks to forms, spaces and colours such that no message is independent of pre-set rhythms, feelings, sensations and affects. Does this mean that a use of them cannot be nomadic?

It is easy to experiment with the sensual characteristics on our smartphones – and hence with our emission and reception of information – thanks to changes available for the full spectrum of backgrounds, figures, colours, sounds speeds and touch. The test is whether that experimentation changes us, leading us to become different, outside the control of pre-established meaning and structures. It is whether we do something new and creative that matters, not the support we use.

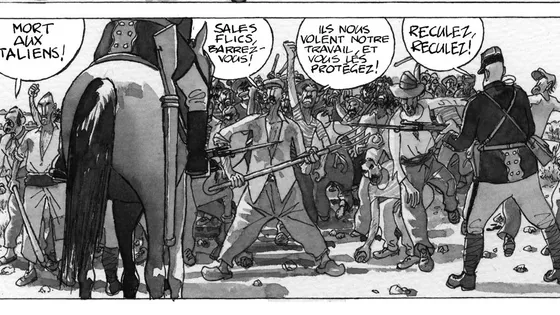

The sheen of screen and paper, ink colours and blank spaces are all distant echoes of other vibrant features. These are explored and experimented with in bande dessinée, such as Baru’s Bella Ciao series, a cultured and timely testimony to Italian immigration to France in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Baru’s art is an invitation to interact with the work in a deeply transformative way. Not always, but sometimes, the reader will change with the work. https://www.futuropolis.fr/9782754811699/bella-ciao-1.html

Bella Ciao gives us clues for answering questions about fiction and reality in BD. Though each bande dessinée is partly fictional, the genre stands out for its hybrid nature, the mixture of many different kinds of drawing and words (and sometimes photography) invites readers into an explicitly multi-layered experience. The overall medium is fabricated, but its reception involves an effect: alertness to levels of reality.

Like documentaries in film and television, BD incites and develops critical awareness about fiction and reality, and about invention and fact. Asking to be refined and reflected upon, it encourages practice attuned to interactions between different types of communication governed by critical questions.

How is this art telling me truths? How is it distorting them? Where are its factual bases? How do these bases filter through layers of words and images? How are these affects, sensations and ideas generated? Are they purely personal? Or are they communal, general or universal?

In more limited cases, or at least most obviously in them, BD encourages this critical practice to focus on specific themes. Baru has long confronted racism and right-wing exploitation of fear and race. He saw early how the rise of tensions around the split between poor suburbs, declining inner cities, isolated villages and more wealthy or racially uniform areas would be exploited politically, in demands for greater law and order, with racist and nativist undertones varying in degrees of explicitness.

His early Bonne année depicts a French banlieue, surrounded by walls and miradors as an excluded and reviled youth race under spotlights and snipers seeking to keep them from city centres, while right-wing politicians spread fear of riots and promises of violent repression on radios and televisions.

In the collection Noir, where Bonne année is reprinted, the banlieue nightclub is the Karaboudjan, the opium smuggling freighter Hergé drew for Tintin’s The Crab with the Golden Claws. This is a hint at another legacy of racism and its embeddedness. Like all the early Tintin stories, not only Tintin in the Congo, it has racist stereotypes and insults. The scandal of depictions of race is also a deep challenge for classical BD. The alertness taught in the experience of bandes dessinées serves in uncovering its historical failings. https://tintin.fandom.com/fr/wiki/Karaboudjan?file=Karaboudjan.jpg

The Bella Ciao volumes continue Baru’s studies of racism and its consequences but with more attention to precise historical roots and precedents. The Aigues-Mortes massacre of Italian immigrants at the end of the nineteenth century is one of the first themes in the series where history, commentary on the present and care for the future come together.

The massacre is commemorated in Aigues-Mortes and beyond. It has been recalled recently as a lesson for present discussions about racism, immigration and violence. The events at Aigues-Mortes were followed widely at the time; in particular, thanks to international awareness of the tensions caused by immigration fuelled by demand for labour and due to a trial where the jury acquitted those who participated in the massacre. Written in 1894, the contemporary relevance of this comment from The Spectator is striking, as is its prescience about more than a century of racist and nationalist violence:

The competitors, though they are wanted, are held to be violent thieves, to be put to death if nothing but death will stop their immigration. The prevalence of an idea like that—and it must be prevalent if a jury acted on it—must intensify the dislike between neighbouring nations to a maddening degree, and can only produce one of two results,—the expulsion of all immigrants, to the great diminution of the national resources, or—and this is the result which will happen—a constant repetition of affairs like that of Aigues-Mortes.

The Spectator, ‘The Decay of Juries’, 6 Jan 1894

Immigration is needed as counterbalance to decreasing birth rates, assuming models of economic development requiring increasing levels of labour, whether this is for the USA, UK or EU: ‘Fact to consider: Many non-EU citizens are “essential workers.”‘ Immigrants are predominantly lawful, settled and valuable members of the community, yet immigrants are reviled and treated as scapegoats in self-serving propaganda.

Baru’s art has been a consistent counter to those destructive lies. He is not alone. Fred Paronuzzi and Vincent Djinda’s 2022 BD De sel et de sang also returns to the Aigues Mortes massacre and the Italian ‘salt convicts‘ exploited by the Compagnie des Salins du Midi.

Returning to the opening question about fiction and reality, the layered quality to BD varies between different works, but it shows how an absolute distinction between fictional and real does not hold. Instead, fact and imagination, history and speculation, testimony and invention, affect and reflection coexist in ways that can prompt readers and creators to question ideas, principles and acts.

As a fast-evolving and varied practice, the definition of BD is determined socially. Due to its inclusion of new and old forms, so long as they become part of a practice covering creators, afficionados, theoreticians, specialist shops and publishers, bande dessinée covers more than comics, cartoons or graphic novels taken alone. More importantly, this span is not only part of the value of bande dessinée as a flexible genre. It also contributes to the interest and dynamism of each of its subgenres and individual works.

For the pragmatic problem of how to gauge the degree of entanglement of fiction and reality two developments in bande dessinée stand out: BD and history; and BD and documentary. In each of these, given the relative nature of pragmatism, it is never a matter of whether bande dessinée is better or best at any of these, but rather how it contributes to new critical interactions between layers of reality and how these can be drawn out.

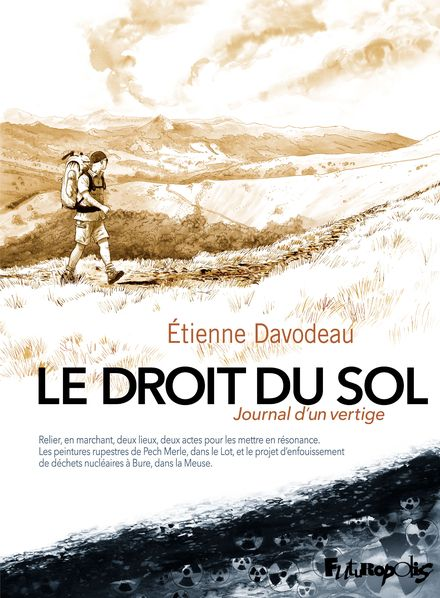

I’ll keep the topic of BD and documentary for a later post. However, for research on the practice, one of the best authors to start with is Etienne Davodeau whose work on documentary is exceptionally self-aware and inventive.

Each of Davodeau’s works is not only a moving, militant and instructive contribution to an important social, political or existential subject, it is also a variation on how to do documentary in bande dessinée form. He takes advantage of its hybrid nature to mix facts, art, critical discussions, fictional debates, real interviews and eyewitness accounts, and images of place, people and events reanimating historical events for contemporary readers.

Davodeau’s documentary on the Bure nuclear waste burial site Le Droit du sol is a model for cautious, self-critical and well-informed militancy. Its literal and imagined paths and its multiple levels of text and image, leave readers with many opportunities to reflect for themselves, while dismantling and remaking the work.

It isn’t quite as well known outside France, despite famous works like Maus, Persepolis and Joe Sacco’s ‘comic journalism’ Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza, but BD can play an important role in the communication of history.

The potential of comics is better understood for current affairs and cartoons have a well-established role in journalism. The comic journalism site is an encouraging focal point for that political and social engagement. Similarly, the importance of comic-based political posters is known and exploited widely.

Recent French studies of history have ranged from highly controversial events, such as the Algerian War, or France during the Second World War (in the epic Il était une fois en France series), or other French colonial wars (like the French defeat at Diên Biên Phu during the First Indochina War), or historical figures from literature (such as Luigi Critone’s return to the Middle Ages in Je, François Villon) and politics (like Raphaël Meyssan’s moving recourse to original engravings in Les Damnés de la Commune), and on to little known and edifying acts and events (for example, the birth of the Algerian national football team during the Algerian war, when most of the Algerian players were signed to French teams, at a time of desperate struggle and terrible loss).

There are numerous French prizes and events recognising historical bande dessinée and its role in disseminating, depicting and narrating history. The major history festival and series of events Les rendez-vous de l’histoire has a prize for the best historical BD chosen each year from a long list of high quality works that ‘rewards the author or authors of a bande dessinée where the quality of the scenario, value of the drawing and seriousness of the historical reconstitution have been appreciated.’ These lists are an outstanding place to start research on historical BD.

There are many other such prizes and discussions, such as the Prix BD historique that recently recognised Jean Dytar’s highly original and thought-provoking J’accuse, demonstrating that the Dreyfus Affair is not behind us (his earlier Florida is also moving, troubling and inspiring); or the Prix cases d’histoire that included Nicolas Juncker’s Seules à Berlin in its 2020 awards. Juncker recounts the horrors of post-war Berlin, for women in particular, in vivid and yet sweeping form, making use of the fast scope, yet arresting images of BD.

BD is distinctive in this ‘reconstitution’ of history and hence many levels of reality due to its composite and layered format. The evolution of different types of bande dessinée takes advantage of cross-fertilisation between them; for instance, in adding documentary reportage to sketching, or painterly effects to storytelling, or succinct imagery to a long form such as autobiography, or the suggestiveness of vignettes to the novel.

This interaction is most evident in the way art and script interact, as the three main creative roles of BD – dessinateur (cartoonist), scénariste (writer) and coloriste (colourist) – contribute to each others work. As told, for example, by Jean-Marc Rochette in Ailefroide 3954, recounting his encounter with Soutine at the Grenoble museum as a child but then carrying this actual event through the artwork and narrative of Ailefroide.

A stark dichotomy between art and reality does not hold. On the contrary, the case of BD shows how a new art-form can enter into a critical, revelatory and constructive relation with different levels of reality. It has done so for history and documentary. It also does so within education and as a learning medium, in and outside schools.

By adding démontage to this layered relation to history in BD, we get to an answer to my initial question. A BD that is about a world-ending catastrophe, like Benjamin Adam’s UOS pictured at the start of this discussion, needn’t be trapped in a single future-bound direction. On the contrary, though bande dessinée is often defined in terms of ‘vectorisation’ or the way images are given a joint direction, démontage comes first and denies any pre-given direction of composition.

Adam’s images are themselves composite. Each one can act as a starting point, or end point, or stand-alone, or explode into parts, or combine with others in novel ways. For BD, time is always there to be made by the reader. The world needn’t end.